On the Strangeness of the Greeks and Other Subjects: Part One

Or, De Novitate Graecorum Dialogus

Dramatis Personae: Antonius Tetrax, Podius Scholasticus

This lightly fictionalized dialogue is based on notes taken from a real conversation in Washington, D.C. with my friend Tanner Greer, a.k.a. Scholar’s Stage. Its title is taken from a line spoken by myself in the dialogue. While we start and end with some observations on Ancient Greek culture, the conversation meanders through various topics such as imperial Roman literature, Daoist sexual ethics, Kantian epistemology, subaltern class of imperial China, rationalism and tragedy, and so on. For ease of reading, I have divided the dialogue into two parts and added sub-headings where the subject matter changes. Any errors in this edit, including footnotes, are my own.

Prelude

Antonius: Greetings, Podius, and please forgive my tardiness. I had to traverse half of the western part of the capital, having rushed down from the hill across the Potomac and taken a route that turned out to be much longer than it appeared on the map. I also did not know there is a shortcut from the Metro station to this playground through the shopping arcade, so I had to take a further detour on top of my already circuitous journey.

Podius: My dear Antonius, there is no need to apologize. It is most normal to rely on whatever electronic map on your phone, even if they are by nature deceptive tools. But is it not a great part of the joy of exploring a new city to wander aimlessly on detours? After all the detour did you no harm, as you’ve made it to your destination in the end.

Antonius: Thank you for the kind words, Podius. How was your day? You told me earlier that you were at this so-called “un-conference”, where instead of having panelists talk on pre-determined topics, participants are encouraged to bring up their own interesting inquiries of every sort sua sponte?

Podius: Yes, and it was greatly enjoyable. Even if the categories of opinions did not seem diverse enough, the sheer quantity of them made up for it. There were over a hundred youths, younger than yourself, who were especially concerned about the development of artificial intelligence—for such is the zeitgeist of our times.

Antonius: I am hardly surprised, Podius, by their zeal in matters such as these, and I applaud them for their curiosity and intellectual commitment; however, I also cannot help feeling a little wistful that talk of technology seems to enjoy a monopoly in our discourse. We have advanced headlong into the age of calculators, economists and sophisters, and left the age of chivalry behind us.

Podius: Given your phrasing, you must know that this sentiment is over two hundred years old. Nearly every age in history has been nostalgic of what came before. Yet I believe that what is behind us is the concern of historians; what lies ahead is that of visionaries.

Antonius: Don’t you think, Podius, that a similar spirit energizes both types of men? Historical novelists and science fiction writers use their imagination to an equal extent, but one looking forward and the other back. Perhaps this single-minded valorization of the future is only a symptom of the restlessness of our current age.

Podius: By no means, Antonius. Speculative fiction has been with us for millennia, just not in the form we recognize it. Didn’t that writer of great wit, Lucian, imagine a journey to the outer space and visitations to fantastic worlds with unfamiliar laws? Even in the twilight of late antiquity the bounds of our imagination already reached distant stars.

Antonius: That is right, Podius. I must confess my knowledge is sorely lacking when it concerns a writer of the fourth century, despite my great enthusiasm for the ancients. In fact, it is a distinct weakness of us so-called classical scholars, fooling ourselves into believing that antiquity ended with the rule of Nero, and nothing worth reading was written afterwards.

Dionysus in Euripides

Podius: Incidentally, I came across a “Literature and History” podcast that vehemently attacks such prejudices, Antonius. In order to remedy this common ignorance, he has even taken the effort to elaborate on obscure authors such as Decimus Magnus Ausonius, who wrote as many as 27 genres of poems, and the Dionysiaca by Nonnus of Panopolis, which is called the last of pagan epics, but even a specialist in Ancient Greek literature may have neglected it in their studies.

Antonius: That is doubtlessly true, Podius. However, I for one would esteem that book, even if by its title alone. I certainly would not dare disrespect anything in connection with Dionysus, a powerful god to whom praise and veneration are due.

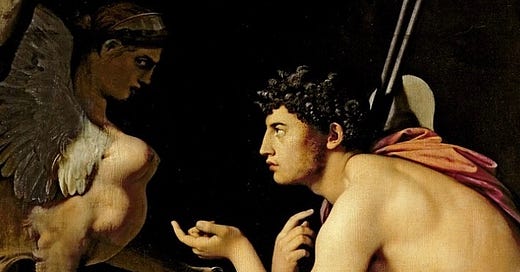

Podius: You surprise me with this view; is there not something intensely horrific and barbarous about Bacchic worship? Judging from your eagerness to rebut my point, it looks like there is a divergence of opinion on the nature of Dionysus. Let it be a litmus test then, when presented with a figure of the wine-god, do you regard him with attraction or revulsion?

Antonius: You are onto something, Podius, as this question, in my opinion, forms the interpretative crux of Euripides’ Bacchae, that tragedy of tragedies. I remember once attending an excellent lecture back in my peripatetic days in the Green Mountains, where my teacher posed the question in this way: are we to read the play as a celebration, or condemnation of the death and dismemberment of Pentheus? Does this not resemble your question of attraction and revulsion for the god?

Podius: It does, Antonius.

Antonius: And the answer, as is often the case when dealing with binaries, is somewhere in between. But my teacher held that the poet leans strongly to the former, namely celebrating Dionysus’ power against Pentheus’ rationalism, for evidently Pentheus’ own worldview brings about his doom. This is rather rich, isn’t it, considering the tragedy was produced at the Dionysian theater at a festival consecrated to the god himself.

Podius: It certainly is, Antonius. But Pentheus’ downfall ultimately comes from his inability to maintain his rationalism. He falls under the mesmerizing effect of the god and wanted to witness the bacchic rites with his own eyes, even when his reason advises otherwise. Curiosity for forbidden knowledge got the better of him, who has even eight fewer lives than a cat.

Antonius: Indeed, Pentheus became too curious after being seduced, so to speak, by Dionysus. Like the wretched Oedipus, Pentheus also destroyed himself by looking for the answer to too many questions.

Digression on Apollo and Artemis

Podius: Be that as it may, you have not answered my question. Perhaps before we discuss your attachment to Dionysus, we can begin with a more fundamental query, Antonius. Which god or goddess do you venerate the most?

Antonius: I think you are asking two different questions: one is the deity that I objectively find the worthiest of praise, and one is the deity that I subjectively find most appealing.

Podius: Let us hear both.

Antonius: How greedy you are, Podius! But I will give you a straight answer. I will nominate the children of Leto. Objectively I value most highly Apollo, and subjectively I am partial to Artemis. The former being the god of reason, poetry, music and in particular, foreknowledge; and the latter being the mystic virgin, as swift in foot as a startled deer and as elusive as a sprite amid the woodlands.

Podius: I notice a curious asymmetry in your answer: when characterizing Apollo, you immediately evoked his symbolic qualities, but for Artemis you jumped straight to her physical attributes. If Apollo stands for reason and prophecy, what aspect of human nature does Artemis represent?

Antonius: You stumped me! She is obviously the goddess of the hunt, but that is hardly a quality inherent in human nature. In fact, I have an answer for you, Podius. Artemis stands for the opposite of Aphrodite. Therefore, she is worshipped by Hippolytus, because he is also a sworn enemy of Eros. However, it is also true that later Artemis became syncretized with the goddesses of the moon and the underworld1; and what that conflation means theologically, I honestly cannot say.

Podius: Just as Artemis is the opposite of Aphrodite; Apollo can be said to be the opposite of Dionysus. Where Apollo represents civilization ascendent, Dionysus pulls us back to barbaric nature. Where Apollo brings order and reason, Dionysus is a harbinger of chaos and madness. Well, in the Bacchae at least, Dionysus represents a menace that is insidious and horrifying, almost like an assassin who would kill you with a smile.

Antonius: Sure, the story ended with horror, but that is because Pentheus resisted the god with a rationalist fervor that one may call unnatural—Euripides surely does not condemn, or is at most ambivalent, about the inherent allure in the irrational! Much better scholars than I have expounded on this point. But let us return to the topic of late antique literature; has the podcaster you alluded to by chance mentioned Ausonius was a centoist?

Cento Nuptialis and Greek Anti-Natalism

Podius: What is a cento? Is it what we call a chapter in a longer poem?

Antonius: You are thinking of the cantos of Dante or Ezra Pound. A cento is the technique of picking sentences and phrases from classical sources, taking them out of context, and restitching them together to tell a different story. In Ausonius’ case, he borrowed Virgil’s phrasing and rearranged it into a narrative of, well, sexual intercourse.

Podius: I can imagine an act of rape being described using language from the second half of the Aeneid, with all the violence and warfare going on.2

Antonius: I don’t know if rape is the appropriate word; this is not a story about the Sabines! It is called a scene at wedding night and is wholly consensual as far as we know. But the description is certainly graphic concerning the consummation of marriage. The author feigned proto-Victorian propriety by warning his readers that what he is about to do is admittedly grossly irreverent and the reader should proceed at his own peril.3

Podius: Yes, the podcaster has mentioned this work. He goes on to claim that such a literary attitude can only be possible with the advent of Christianity—

Antonius: Let me guess, does he think Christianity signifies the shift to a new faith, and by extension, new worldview that permeates literature? I suppose the logic goes thus: in order for a Latin writer to have the audacity to turn canonical and traditionally moral poet like Virgil upside down, he must be equipped with a new kind of spiritual fortitude; and the only source for such fortitude against paganism is Christianity.

Podius: Interesting notion, but no. He dwells at length at the disgusting nature of Ausonius’ wedding bed. Ovid, Propertius, Horace and the other Roman poets described their encounters with the opposite either as episodes of idyllic romance or as moments of personal conquest; Ausonius is different. Ausonius, he says, provides a “graphic and almost sinister depiction of sexual intercourse.” Depicting “a bride’s loss of virginity as a violent, mutually defiling process” would have made no sense to the pagans of Ovid’s day—but was this not the view of the average Christian monk? Perhaps Christian attitudes had seeped into the mind of this pagan.

Antonius: I am not sure I agree, Podius. In that respect Ausonius was perhaps more classical than the commentator gives him credit for. The military analogy of love goes a long way back. The miles amoris, “soldier of love”, has been a common trope since the golden age of Latin literature and is ubiquitous in Ovid’s love elegies. And while his Ars Amatoria primarily deals with the art of “seduction” rather than straight-up sexual assault, the mythological tradition is full of rape scenes, a fact that he took great advantage in the Metamorphoses. In fact, nearly every intercourse between a god and a mortal woman is not strictly consensual, be there an element of violence or deception.

Podius: Now that I think of it, there is something curious and striking about the sexual ethics of the tragedies, and the Greeks more broadly. The Old Testament depicts a great amount of depravity, sometimes in the form of positive models, and sometimes as an admonition for the wicked. But the relationship between the sexes is, well, for the lack of a better word, healthier. For example, there is no inherent violence in the act of procreation, which the Greeks seem to abhor. Did Euripides not write in his Medea that giving birth once is more frightening than facing enemies in battle three times?4

Antonius: Yes, and this idea of birth being a monstrous, nightmarish thing is even present in Aeschylus, where Clytemnestra literally has a nightmare of giving birth to a serpent, and we know she ends up being murdered by her own son.5

Podius: Precisely.

Antonius: Perhaps it is something we should regard in the context of Greek pessimism in general, such as the chorus’ notion that “not to be born is best by far” in Oedipus at Colonus, or Solon’s view in the court of Croesus that dying young is the second best thing a mortal can hope for.6 Pathologizing the natural act of life and procreation, exhibiting cases where a natural order is upended, seems to be a hallmark of tragedy.

Confucian and Daoist Attitudes on Childbirth

Podius: Ah, then here is a great question for you, my friend: do you find any parallels of this sort of pessimism in ancient Chinese thought?

Antonius: Certainly not among the Confucians, who are about as natalist as it gets. “There are three things which are unfilial,” says Mencius, “and to have no posterity is the greatest of them.”7 “Giving life is great virtue” 大德曰生: this phrase from the Book of Changes is inscribed on outside the Forbidden City even to this day. But even Daoists, despite their general cynicism, probably thought procreation, as the natural process of life, is a great virtue.

Podius: That is fair. But let us depart slightly from strict pessimism about childbirth and consider the larger worldview, one that sees chaos, full of dark mysteries, fearsome and perhaps unknowable, standing above all. In other words, a worldview that stands in stark contrast to the rational virtues of the Hellenes, one that is Dionysian as opposed to Apollonian, to borrow from a hackneyed Nietzschean dichotomy. Can we find parallels of Bacchism in ancient Chinese thought? I think the Apollonian element of Chinese thought has to be Confucianism, where things exist in harmony according to a predetermined, well-defined, rational order. What then is the Dionysian aspect?

Antonius: If Confucianism corresponds to the cult of Apollo, then naturally we would think Dionysus corresponds to Daoism. We should probably examine more closely what Dionysus really stands for. He is a transgressive figure who may be called, in our contemporary parlance, gender fluid. After all that is the philosophical form of drunkenness: being in a liminal state of mind that lets loose of social and spiritual regulations. That seems a bit like the fluidity enjoyed by the giant bird and sea monster in the opening chapter of the Zhuangzi.

Podius: The Daoists are indeed anti-Confucians. Like the worshippers of Dionysus, they also have some bizarre notions related to sex. By the way, Antonius, did you know that the Daoists think the most wonderful in the world is the erect penis of an infant?8

Antonius: I did not, and to be honest, it is rather alarming to hear.

Podius: Yes, and the reason being an infant’s erection represents potency without intention, and the annihilation of intention reveals one’s nature. The Daoists do not see reproduction as abhorrent, but rather a mystery, one that is even celebratory.

Antonius: Yes, the Laozi is also full of adulations of the female genitalia in the form of the “mystical feminine” 玄牝, the cavern, the river… the true meaning of which could not have been more obvious but had vexed prudish scholars for a long time. Now, the ubiquitous particle ye 也 has long been thought to represent the vagina.9 Some fanciful readers in the twentieth century think the character qie 且 originates from the male member.10 That probably comes from reading too much Freud. But to ignore the sexual meaning of the Laozi seems to be throwing the baby out along with the bathwater.

Podius: There are also Daoist treatises on the techniques to preserve semen, or jing 精 “essence”, during intercourse—how to make the woman reach multiple orgasms but not the man; I once explained this to a friend, and he remarked the book must have been written by a woman.

Antonius: Alas, that we may never know. Would you say this attitude towards childless sex somewhat resembles the Greek’s pessimism in its negation of human will, which arguably evolved into the essential concept of Western life?

Podius: Perhaps, but I conjecture the Daoists are not overtly Bacchic enough: they are at most without reason, but not a reaction against reason.

Antonius: I do not disagree, but we have to take into account the fact that Greek rationalism never arose in ancient China. As such, there could not have been an intentional reaction against reason. However, if we assume that the closest equivalent to Greek rationalism in classical China was the Confucian social construct, functionally speaking at least, then later Daoists of the Six Dynasties were immensely self-conscious about their rebelling against Confucian order.11 By this I mean, if there is something in ancient Chinese philosophy that corresponds to rationalism, it is probably this institutionalized version of Confucianism, paired with the imperial bureaucracy. But I just had an eureka moment, Podius. I know what the candidate for a Chinese version of Dionysian cult is.

(For the content of Antonius’ revelation, dear reader, please turn to Part Two of the dialogue.)

Selene (Luna in Latin) and Hecate respectively. The syncretized Diana-Luna-Hecate deity in Rome is called Trivia, “Goddess at the Crossroads”.

Rome’s national epic Aeneid by Virgil can be divided in two halves, each modeled after one of the Homeric epics: the “Odysseian” half (Books 1 to 6) tells of Aeneas’ travels as a refugee from Troy to Carthage and arrival in Italy, and the “Iliadic” half (Books 7 to 12) narrates the war between Trojans and Italian tribes and ends with Aeneas’ victory over his foe Turnus.

Titled Parecbasis or “digression”: “So far, to suit chaste ears, I have wrapped the mystery of wedlock in a veil of roundabout and indirect expression… the remaining secrets also, of bedchamber and couch, will be divulged in a selection from the same author [Virgil], so that I have to blush twice over, since I make Virgil so immodest. Those of you who so choose, set here and now a term to your reading: leave the rest for the curious.” (tr. Hugh G. Evelyn White, from the Internet Archive)

ὡς τρὶς ἂν παρ᾽ ἀσπίδα / στῆναι θέλοιμ᾽ ἂν μᾶλλον ἢ τεκεῖν ἅπαξ. (Medea 250–251)

See Aeschylus, The Libation Bearers. The dream of Clytemnestra is described in lines 523–534.

μὴ φῦναι τὸν ἅπαντα νικᾷ λόγον (Oedipus at Colonus 1225). For the story Solon tells to Croesus about the deaths of Argive youths Cleobis and Biton, see Herodotus 1.31.

Mencius, “Li Lou A 離婁上” (English translation)

Dao De Jing, Chapter 55: “[The infant’s] bones are weak and its sinews soft, but yet its grasp is firm. It knows not yet the union of male and female, and yet its virile member may be excited (全作), showing the perfection of its physical essence (精之至也).” (tr. James Legge) The text is notoriously laconic and multivalent; its central concept de 德 can mean (literal) potency, as distinguished from, e.g. Mencius’ notion of childish innocence of “the heart of a naked babe” 赤子之心.

This was the traditional interpretation according to Xu Shen, Shuowen Jiezi.

Notably Guo Moruo, archaeologist, poet, court toady and quondam Chairman of the Chinese Academy of Sciences; and Li Ao, Chinese-Taiwanese essayist known for his inflammatory social commentary.

Many entertaining accounts are found in the Shishuo Xinyu, a book of anecdotes compiled in the 5th century, for example in the chapter entitled “The Free and Unrestrained” 任誕.

I believe Antonius is right that Ausonius was more classical than Christian

From the Phaedo: “if we are ever to know anything absolutely, we must be free from the body and must behold the actual realities with the eye of the soul alone.”

But Podius is not wrong to connect Ausonius to the Christian monk - perhaps the monk is more Hellenistic than he is Hebrew!

Here is a wonderful book review on how Greek sexual pessimism and Hebrew marital traditionalism competed for influence in early Christianity:

https://www.thepsmiths.com/p/joint-review-origens-revenge-by-brian?utm_source=publication-search

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liang_Qichao also very worth reading for the Chinese literature context